How Spotify hacked our ears

Journalist Liz Pelly argues that algorithms and "Perfect Fit Content" shape what we hear

Listen on Apple Podcasts, ironically, yes Spotify, or anywhere you get podcasts.

Every morning, millions of us wake up and hit play on our personalized Spotify Daylists, those algorithmically-generated soundtracks that promise the perfect music for every moment. For me, Sunday mornings usually start with Ethiopian jazz, but I've noticed something strange happening after a few tracks. The algorithm drifts into a sonic uncanny valley - think bland piano covers of Beatles songs and suspiciously generic "chill beats." According to journalist Liz Pelly's fascinating new book Mood Machine, this musical purgatory isn't an accident. It's part of Spotify's deliberate strategy to reshape not just how we discover music, but what music gets made in the first place.

When Spotify launched in 2006, it wasn't even meant to be a music platform. Founded by advertising executives in Sweden, according to its patent filings, it could just as easily have been a video service. But music's smaller file sizes made it perfect for testing a streaming model in the dawn of Web 2.0, even if that meant initially populating the service with tracks downloaded from Pirate Bay (yes, really).

The platform has gone through several distinct evolutionary phases, each reshaping the sound of popular music. By 2013, Spotify had moved beyond being just a search bar to become a mood-based recommendation engine. Landing on influential playlists like RapCaviar could make or break careers, leading to what one former employee calls the "peak playlist era" (2016-2019). While it was suing to keep songwriter royalties low, during this period, Spotify hosted songwriting camps themed around specific playlists like "The Most Beautiful Songs in the World" - pushing artists toward a particular "Spotify sound." Instead, artists were encouraged to create "soft" and "muted" tracks optimized for background listening.

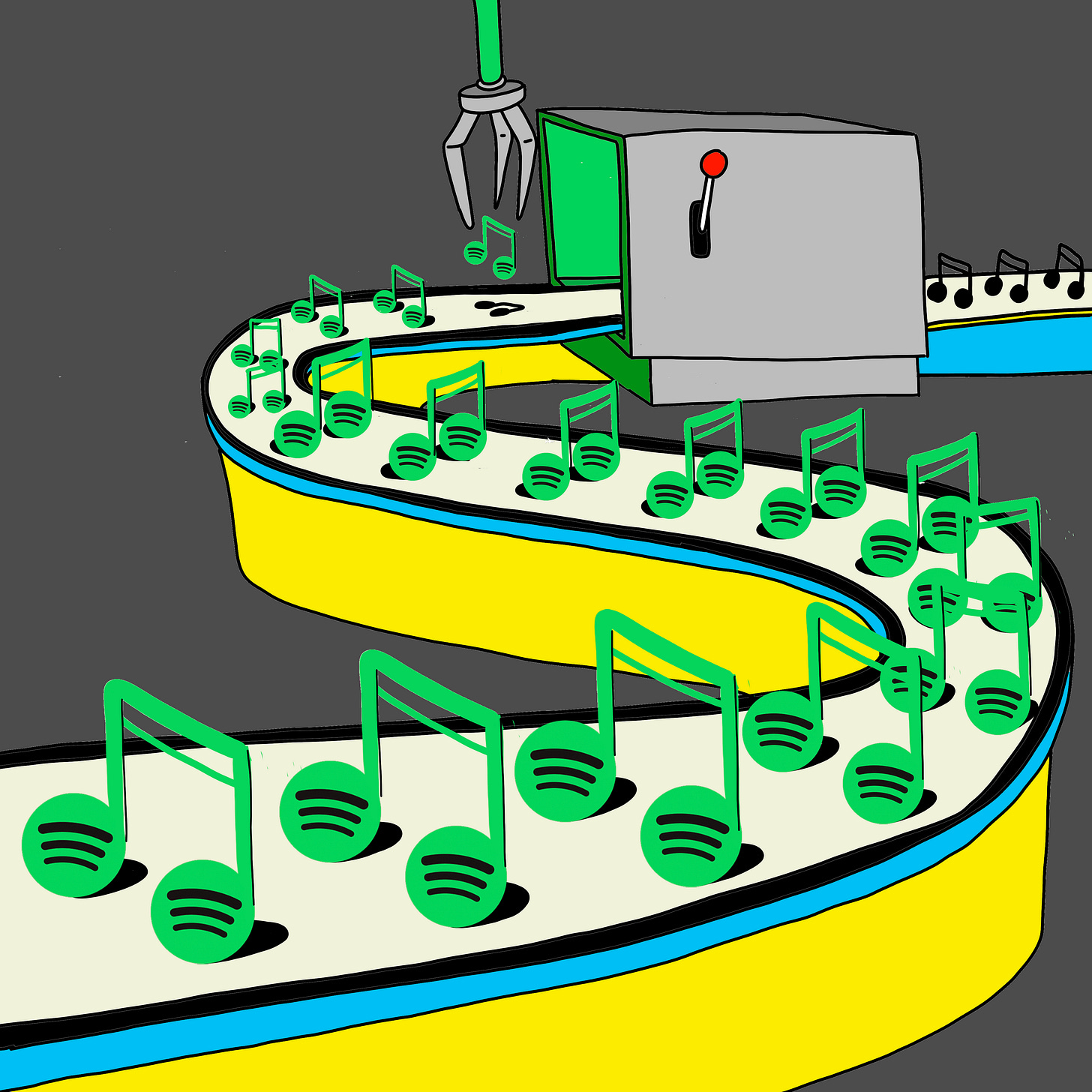

But here's where things get really interesting: Many of the tracks on Spotify's most popular mood playlists aren't coming from the artists you think. Through companies like Epidemic Sound, Spotify commissions music from a small group of composers who create tracks under hundreds of different artist names. For example, Pelly found jazz musicians hired to crank out dozens of tracks per day for “chill jazz playlists” that were made to be simple, without complicated chord changes, nothing too engaging - in other words, everything that makes jazz, jazz had to go. If this music’s blandness isn’t alarming, then consider Spotify’s business incentive. This "perfect fit content" (PFC) comes with special royalty arrangements that are more profitable for Spotify. They have an incentive to promote PFC to playlists to reduced royalty payments. While the company says this represents a small percentage of total streams, even a small percentage on Spotify is significant - for comparison, Taylor Swift's entire catalog accounts for just under 2% of total streams, more than all jazz and classical music combined.

The push for "perfect fit content" is just one way Spotify tries to reduce its royalty obligations. Through its Discovery Mode program, artists can gain more algorithmic promotion by accepting a 30% lower royalty rate — a practice that generated over 61 million euros in profit for Spotify in 2023 alone. Meanwhile, Spotify has actively fought to keep royalty rates low through legal channels. Most recently, in January 2025, Spotify won a significant lawsuit against music licensing groups over its bundling practices. By packaging music with podcasts and audiobooks, Spotify can spread subscription revenue across all audio content, effectively lowering per-stream payments to musicians while maintaining profits.

These practices reflect a fundamental tension in Spotify's business model. As a public company, it faces constant pressure to improve profit margins. But unlike podcasts and audiobooks, which come with more favorable licensing terms, music streaming requires significant royalty payments. The result is an ongoing push to reduce music costs through various means, from commissioning "perfect fit content" to legal battles over royalty rates to offering promotional opportunities in exchange for lower payments.

This drive to maximize profits while minimizing costs has shaped Spotify's latest evolution. Today, we're in what Pelly calls the "hyper-personalized era," dominated by algorithmic features like AI DJ and Daylist. These tools fulfill what Spotify executives have long called their ultimate goal: "self-driving music" where users simply hit play and let algorithms determine what they hear. The timing isn't coincidental. In the 2020s, as TikTok became the new kingmaker for music discovery, Spotify has pivoted hard toward algorithmic personalization to maintain its edge.

These questions matter because they fundamentally affect not just individual artists, but the entire musical ecosystem. When you're studying to those perfect lo-fi beats (like the one I admittedly tried making for this episode), you might actually be listening to commissioned content designed specifically to maximize streaming profits. It's a long way from the Ethiopian jazz I actually want on my Sunday mornings.

The platform that was born from piracy has become something far more influential than a simple streaming service. It's now a mood machine that shapes the sound of contemporary music through a complex web of algorithmic recommendations, playlist placements, and commissioned content. For more on how streaming is reshaping song structure and production, check out our previous episode "When the Drop Broke Pop." Understanding how this machine works is crucial for anyone who cares about music's future - whether you're a casual listener or a musician trying to navigate the streaming economy.

Want to dig deeper into how streaming shapes sound? Check out Liz Pelly's Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Cost of the Perfect Playlist or listen to the full conversation on the podcast on Apple Podcasts, ironically, yes Spotify, or anywhere you get podcasts.